– HISTORY

The Organ

The new organ was installed ready for the chapel’s re-opening in November 1821. It was customary for instruments to be completed and demonstrated in the organ-builder’s workshop before being dismantled and transferred to their permanent location, and this is probably what happened with the St John’s organ. A musical gentleman-amateur from Chichester, John Marsh, travelled up to London in November to see Mr Lincoln about a job the workshop was undertaking for his son, a clergyman; he was put out to find HCL preoccupied in the chapel which had just been repaired, painted & enlarged, by bringing forward the galleries, & was to be opened the next day, with a large & complete new organ … on which his people were hard at work in finishing, & which therefore prevented his completing that at my Son’s chapel, to hear the effects of which, with the Venetian swell, was the principal reason of my coming up this time’. Despite disappointment at the lack of progress on his son’s organ, Marsh took the opportunity to attend the opening at St John’s Chapel the following day. John Purkis (1781-1849), a blind organist who held appointments at St Clement Danes in the Strand and St Olave, Southwark, played. Marsh noted in his diary:

After service, I went up to the organ loft where I saw Mr. Lincoln, whom I told that if the sound of this fine instrument had not put me into good humour again, I should have expressed my great displeasure at his having brought me up to town to no particular purpose, as he must have known what he had to do in completing this organ; [in] answer to which he told me that he might yet have been able to finish our chapel organ, had not one of his best workmen been taken ill at the beginning of the preceding week.

Marsh returned to Bedford Row in May 1822 to hear Charles Wesley (Organist of St Marylebone Parish Church) and Purkis play ‘on the fine new organ there … before several amateurs’; he missed Wesley’s performance but was ‘much pleased with Purkis’s playing. A few days later (13 May), he went again, this time to meet Lincoln and try the organ for himself; as a result he was gratified at being able to give a favourable account of it in writing to Mr. D. Wilson [sc. The Revd Daniel Wilson, the minister], who had requested me to do so, to assist in counteracting some injurious reports respecting it & the sale of the old organ, set on foot by Miss Cecil the present organist, who seemed much prejudiced against Mr. Lincoln, perhaps (as was suggested to me) from his not complying with a demand of hers for an allowance, as organist, out of the purchase money, although she had no concern in bespeaking the organ, or choosing the builder of it.

Marsh refers here to the practice (common throughout the nineteenth century) of organ-builders paying ‘commission’ to organists who helped to secure them contracts. The sum might be as much as 5% of the contract price. Although frowned upon by vestries and those responsible for paying for the organ it proved hard to eradicate and clearly Miss Cecil felt it was her due. Her prejudice against HCL is slightly surprising in view of the fact that he was the only organ-builder whose name appears as a subscriber to her Twelve voluntaries. Marsh’s diary provides a rare glimpse of HCL in his environment, and his descriptions of the installation, opening and reception of the new organ are particularly valuable in view of the lack of other documentation. Lincoln’s new organ would have stood in a gallery. The chapel was square in plan, with rows of windows along the south wall on Chapel Street, and a large window between the two eastern entrances in Millman Street. The north and west walls abutted adjoining properties and may therefore have lacked gallery windows; if so, it is possible that the organ was placed in one of these galleries.

The organ case must have made a strong visual impression in the relatively small interior of the chapel. The architectural front is a curious confection of elements: pilasters, sun-bursts, palm fronds, acanthus leaves and husks decorate a wooden case which, in form, consists of a wide central flat of pipes, with smaller double-storied flats and a semi-circular outer tower to either side. The pipes are gilded and the wood is finished with a dark stain. Such stylistic eclecticism is entirely typical of the period.

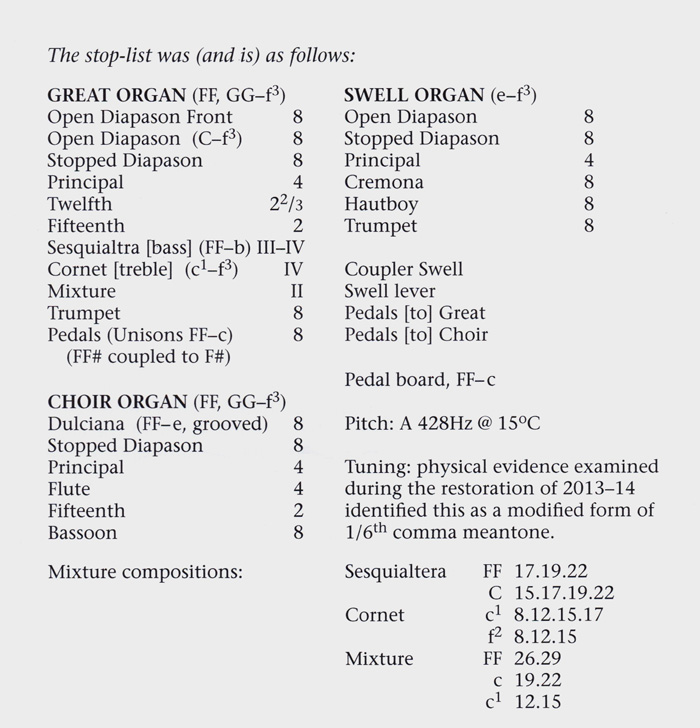

Lincoln’s organ had superficial similarities to the Harris instrument that it replaced: the number of stops was exactly the same (although four of Harris’s Choir registers were ‘borrowed from the Great), and both Swell keyboards commenced at tenor e. However, HCL incorporated a number of progressive features in his scheme. The Great mutations and cornet of the earlier organ gave way to a second open diapason and mixture, perhaps in the interests of congregational accompaniment. The cornet – a brilliant, reedy solo stop composed of five ranks of pipes at different pitches – had gone out of fashion and had been absorbed with its tierce into the treble of the main chorus mixture; organists preferred semi-orchestral solo stops such as the cremona, hautboy, trumpet and bassoon that HCL carefully provided. (Miss Cecil’s voluntaries, with their solo passages for the bassoon and cremona, reflect this preference.) The provision of pedals and pedal pipes was also forward-looking. Pedals had been virtually unknown in English organs before 1790; when first introduced, they were mainly seen as a useful accessory for holding down the bass notes of the Great keyboard (again, Theophania Cecil’s voluntaries provide examples). Large-scale wooden pedal pipes, mainly of unison (8’) pitch, began to appear after 1800; at first they were seldom more than an octave-and-a-half in compass – as at Bedford Row – but they lent weight to the bass in accompaniment. Lincoln’s organ would also have been distinguished from Harris’s by its tonal refinement, a certain delicacy in some of the registers (e.g., the dulciana), and a smoother, slightly more opaque tone, all of which reflected the musical taste of the early nineteenth century.

The cost of the organ is unrecorded. To judge by other Lincoln work it would probably have been around £600; a later statement that it cost £1200 is almost certainly wide of the mark. The use of the organ in divine worship would have been comparatively modest. According to one contemporary, who was probably referring to the Harris organ rather than its successor, The prayers were read without any chaunting; a psalm was sung after the second lesson, as well as before the communion service and sermon; the organ, which was one of the finest old instruments in England, was played by Miss. Cecil, a mistress of the art, who caught up and carried on the sentiment and feeling of the hour; and the whole was grave, devotional, and edifying. There would perhaps also have been a short voluntary at the beginning of the service, and a more extended, livelier piece at the end; some churches retained the ‘middle voluntary’ before the first lesson. Not being a parish church, St John’s had no charity children to provide a choir, and, in any case, the principal focus in proprietary chapels was always the sermon, delivered by a fashionable preacher.

St John’s Chapel remained a magnet for Evangelicals of the Established Church, though its influence declined after the departure of Daniel Wilson to be Vicar of Islington in 1824. In 1848, his successor, The Revd the Hon. Baptist Noel, felt compelled by the Gorham Controversy to leave the Church of England; he became a Baptist (appropriately enough) taking much of the congregation with him. His eventual successor was the Revd Joseph Butterworth Owen, and it was during his necessarily brief tenure (1854–7) that disaster struck. A contemporary account describes the event that was to terminate the chapel’s existence:

One Thursday evening in November, 1856, when the verger was about to ring the bell and summon the congregation for the usual week-day evening service, he could produce no sound. Still many were assembled, and divine service proceeded; but when the Minister ascended the pulpit, he perceived, from signs not to be mistaken, that the whole of the immense and massive roof had shifted and sunk, and might at any instant crush him and the whole congregation. A very short sermon naturally, and most wisely, followed this discovery; and that was the last sermon preached, or ever to be preached, in a chapel where the TRUTH AS IT IS IN JESUS, had been so long and so faithfully held forth by a succession of able and pious ministers.

It would seem that a decision was taken the following year not to rebuild; by the second half of the nineteenth century, proprietary chapels had fallen from episcopal favour, and this may have influenced the fate of St John’s Chapel. Owen was found another post, and in 1863 the building was demolished. Despite the unsafe condition of the chapel, it proved possible to remove the organ, which was offered for sale.

Extracts from the book The H.C. Lincoln Organ in Thaxted Parish Church, Essex. By Nicholas Thistlethwaite and Dominic Gwynn. The book is still available, please use the contact page to enquire.

– HISTORY

Thaxted

Lincoln’s organ was purchased for £230 for Thaxted Church in Essex; £150 was donated by Lord Maynard, and the remainder was raised by voluntary contributions.32 It was opened on 9 June 1858 with a service at which Mr J. T. Frye, Organist of Saffron Walden Parish Church, presided, ‘assisted by a full choir’.

The celebrations commenced with morning service attended by a congregation said to number ‘from 1,500 to 2,000 persons’. The choir performed Samuel Webbe’s ‘When the fullness of time was come’ and ‘an anthem from Mozart’s 12th service’. Perhaps inevitably, the assembly joined in the Old Hundredth ‘to the proper tune by Luther’. The contemporary newspaper report then spends precious column inches listing individual members of ‘the fashionable company’ who attended the service, afterwards repairing to a marquee in the vicarage grounds ‘where an elegant luncheon awaited them’. Suitably refreshed, they returned to the church for ‘a further display of the powers and capabilities of the organ’, now joined by ‘many others, including hundreds of the humbler class’. Frye opened with the overture to Handel’s oratorio, ‘Samson’, and then ‘Mr. Holdich, the organ builder of Euston Road, Kings Cross, who erected the instrument at Thaxted, and effected judicious improvements … played a pastoral symphony’. Various other pieces followed, including organ duets played by Frye and his cousin, Miss Mary Ann Frye, who had been appointed organist, and the concert concluded with the ‘Hallelujah’ chorus. The correspondent ended his account euphorically (if not very grammatically) with the reflection that ‘this musical treat throughout has been one … which of the kind has not been paralleled in the memory of any living inhabitant of Thaxted’.

The description of the organ largely tallies with what is known of Lincoln’s instrument. There is a puzzling reference to the addition of coupling stops: Holdich’s ‘judicious improvements’ may have included the replacement of some carved elements of the case with fretwork, but it is difficult to imagine what other changes there might have been, unless some alterations were made to the wind system.

Clearly funds were limited and this ensured that comparatively few modifications were made, but the organ was fortunate to fall into the hands of George Maydwell Holdich (1816-96). In an age of progress, Holdich was a more conservative figure, keen to preserve the tonal characteristics of older English organs and not excessively concerned to flatter the vanity of organists by providing battalions of console accessories. He was also something of an antiquarian. Holdich was probably content to install the Lincoln organ much as he found it, perhaps calculating that it was more than adequate to meet the modest needs of a country church.

Thaxted Parish Church: the H. C. Lincoln organ before it was removed for restoration.

Image credits:

— Michael Bailie.

– HISTORY

Gustav Holst

In 1914, the composer Gustav Holst (1874–1934) took up residence with his family in Thaxted. Conrad Noel had become Vicar in 1910, and was already preaching the gospel of ‘Catholic Socialism’ and making strenuous efforts to revive a more colourful style of worship embodying what he believed to be mediaeval liturgical practices; daily mass, plainsong, and Morris dancing (for recreation) were part of his programme, and on St George’s Day, the Red Flag and the flag of Sinn Fein were displayed in Thaxted Church alongside St George’s flag.

Holst encountered Noel in church on Whitsunday when he heard the singers’ attempts at plainchant. To Noel’s delight, he offered to assist with the music, and so (in the Vicar’s words) ‘for many years he was master of the music and showed infinite patience at the music practices’. On his first visit to Thaxted Church, Holst had been deeply impressed by its light and spaciousness, and he conceived an ambition to mount a festival of music there. In 1916, he organised the first of three Whitsuntide Festivals. These were long week-ends of amateur music-making, in which local singers combined with Holst’s pupils from Morley College and St Paul’s Girls’ School to perform Bach cantatas, Byrd masses, motets and anthems by Victoria, Palestrina and Purcell, English madrigals, and some of Holst’s own compositions, including ‘This have I done for my true love’ and ‘Turn back, O man’.

During his years in Thaxted (1914–25), Holst often played the Lincoln organ (which he referred to as ‘his’ organ) for choir practices and services. On occasions, his friend and fellow-composer Ralph Vaughan Williams accompanied him to the rehearsal, and the two men took it in turns to play and conduct. Conrad Noel’s daughter also recalled Holst giving impromptu recitals on the organ in the dusk during air raids.

In 1925, Holst moved to Little Easton. From time to time he returned to Thaxted to play ‘his’ organ. One of his visits gave rise to an interesting episode. Jack Putterill (Holst’s successor as ‘master of the music’, and Noel’s curate, son-in-law, and eventual successor as vicar) had successfully introduced a band of instrumentalists to play with the organ and singers at the great festivals such as Christmas, Easter and Whitsun. But a problem arose when clarinetists wanted to join. Putterill continues the story: Unfortunately (the organ) is of low pitch, in fact almost a semi-tone down. Most instruments could be tuned to this low pitch but not the clarinets, and I had to transpose all their music. Everyone groaned about the low pitch, so I consulted Mr. Arnold the organ builder and asked whether it would be possible to raise the pitch a semi-tone by just [moving the trackers up one. He said he thought he could, and carried out the modification with great skill. The result was pleasing and all the orchestra were happier because the clarinets could join in without trouble. Although the organ generally had adapted well to the change, one of the Pedal Pipes remained at its original pitch, but ‘as it was seldom played’, Putterill was unconcerned. However, on Christmas Eve, Holst arrived unannounced to play the organ and immediately discovered the note. Putterill’s account continues: He kept on playing the offending note and turning to me he said, ‘What is this? Who has been tampering with my organ?’ He was so concerned that I thought it best to make a full confession of what I had done – with the help of Mr. Arnold. I explained how the clarinets could not be tuned to this low pitch and that we had raised the pitch, so all could play. He nearly passed out.

He sternly reprimanded me for tampering with the organ – his organ – said I should not have done any such thing, and that further it was a great mistake to bring clarinets into our orchestra. He told me immediately to alter it back again. Then as his kindly character and custom was he said, ‘Yes, I see why you did it, and it is a very good thing to get everyone to play, but I should alter it back.’ This, of course, I did.

It is fascinating to discover that Holst not only admired the musical character of the Lincoln organ, but, with his knowledge of what is today termed ‘early music’, understood the importance of preserving its original pitch.

Image credit:

— Michael Bailie.