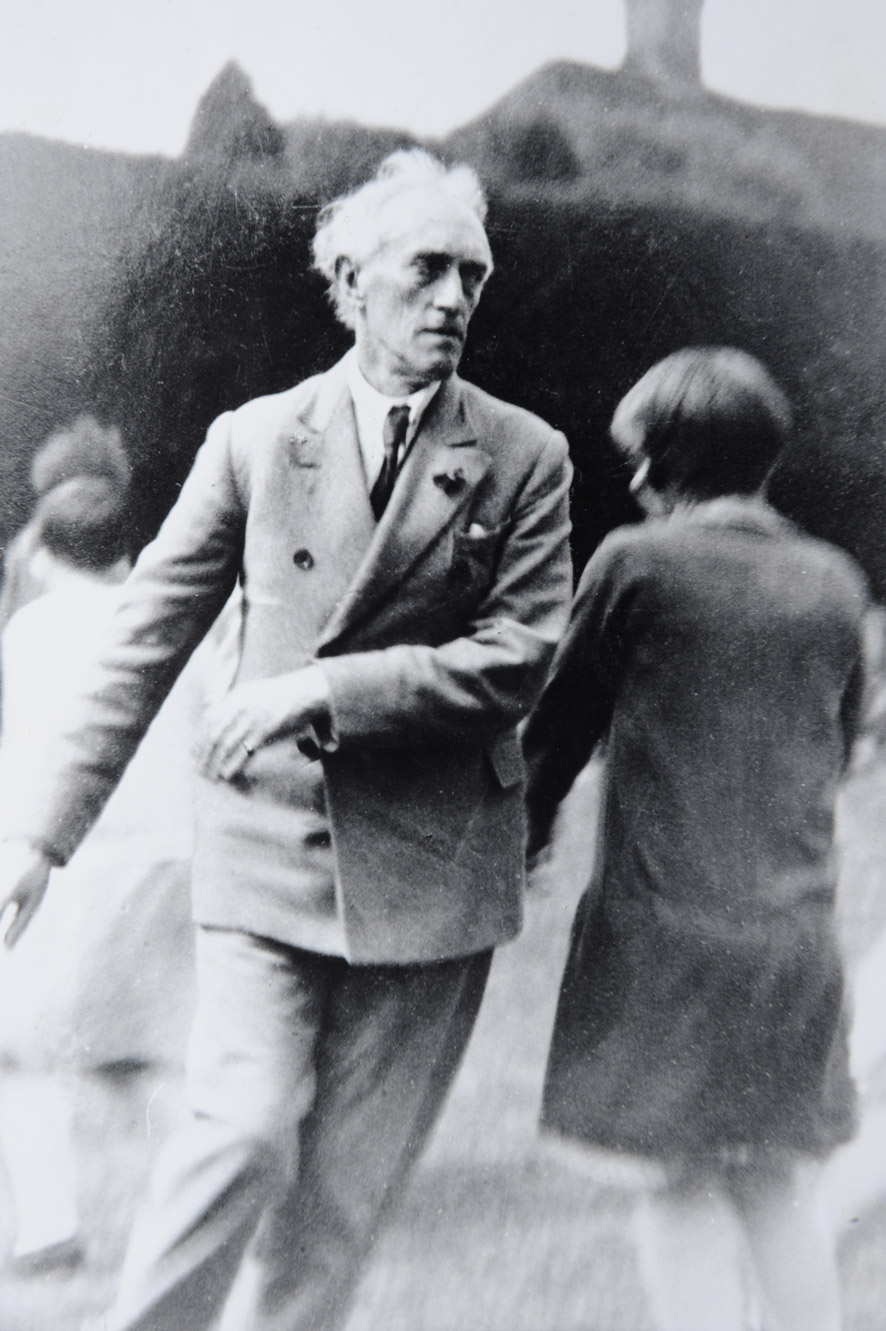

– GUSTAV HOLST

Gustav Holst and Thaxted — by Imogen Holst

The editor of the Thaxted Bulletin has asked me to write something about my father for the spring of 1974, in celebration of the hundredth anniversary of his birth. His first glimpse of Thaxted was in the winter of 1913, when he was on a five-days walking holiday in north-west Essex. He stayed a night in the ‘Enterprise’ in Town Street and he liked the place so much that he made up his mind to return there. In the following year a friend told him of a cottage belonging to the writer S.L.Bensusan, which was to let Although it poured with rain on the day he and my mother went to see it, they immediately knew that Thaxted was the right place to live, and Monk Street Cottage became our home for a short time.

Unfortunately it was burnt down more than forty years ago and the recent road-widening had destroyed all trace of the garden. The cottage dated from 1614: it had a thatched roof, and open fire-places, and a wonderful view across meadows and willow trees to the church spire in the distance. In the fields beyond our garden we could watch the farmer sowing the seed broadcast. Farm horses moved a leisurely pace between the hedges of what is now (in 1974) the A.130, and there was a carrier’s cart on Wednesday afternoons. Here, in this quietness, my father, who had been rejected by the recruiting authorities as unfit for war service, was able to work at The Planets.

The neighbours were at first suspicious, because our name was then ‘von Holst’. They told the police dramatic stories of the stranger who walked alone for mile after mile. The police, however, merely noted in their report: ‘Many rumours are current about this man, but nothing can be traced against him.’ Meanwhile, my father and Conrad Noel had become friends, and he began helping the singers in the church choir, who spoke of him affectionately as ‘our Mr.Von’.

It was in 1916 that he organised and conducted the first Whitsun Festival in the church, bringing his London pupils from Morley College (including Jack Putterill) to join with the Thaxted choir in Bach cantatas and Byrd’s Mass for Three Voices. The music was performed as part of the church services, the only listeners were the congregation.

‘We kept it up at Thaxted about fourteen hours a day,’ my father told a friend, ‘and I realise now why the bible insists on heaven being a place where people sing and go on singing’.

After the unforgettable weekend he wrote several works specially for Thaxted, such as the Festival Chorus Our Church-bells in Thaxted at Whitsuntide say, Come all you good people and put care away, and Tomorrow shall be my dancing day, which he considered his best ‘part-song’. He dedicated this to Conrad Noel. (It is commemorated on one of the Thaxted bells, with the inscription ‘I ring for the General Dance’.

The 1918 Whitsun Festival was the last to be held at Thaxted, but he often helped with the music in church, and he nearly always played the organ at Christmas. (one of his listeners has recently reminded me: he made that organ speak). There were hilarious parties at the Vicarage. Last night I was acting in charades,’ he wrote to a friend.’I was a curate holding a dancing class in a teetotal night club. Conrad was a performing lion. Such is life – in Thaxted at Christmas!’ And he joined in the carol-singing through the streets, inviting the choir for hot drinks and mince-pies in our home. This was no longer a cottage at Monk Street: it was ‘The Steps’, now known as “The Manse’.(Town Street was still quiet and traffic-free in those days).

The plaque near the front door of ‘The Manse’ is on the wall of what was his music-room from 1917 to 1925. It was a peaceful place for composing. He spent the whole of 1924 there, recovering from an illness, and working at his Choral Symphony. ‘It has been wonderful’, he wrote to a friend, ‘to sit all day in the garden and to watch the symphony grow up alongside of the flowers and vegetables, and then to find that it is done!’

We left Thaxted in 1925, but he never lost touch with his friends. In the last winter of his life he was hoping to get to the church for Christmas. But he was not well enough, and he died five months later, in the Whitsun week of 1934, at the age of fifty-nine. His tradition lives on. The Kyrie from the Byrd Mass is still sung every Sunday, and his ‘carols for Thaxted’ are played every Christmas morning. The 1917 music-banner is still carried round the church during processions: its faded silk has been beautifully renewed, and Bach’s words, which he chose, still announce that ‘the aim of music is the glory of God and pleasant recreation.’

– THAXTED

The Legacy that Holst bequeathed to Thaxted

For the past century his music has been adored, quoted, borrowed and pilfered, has been the inspirational compositional source of film music more than any other in the entire canon of classical music. But more importantly for us, Gustav Holst has been our guiding inspiration for music making in Thaxted.

It was once jested to a completely unknown, bespectacled young musician playing trombone deep in the theatre pits at the back of the brass section of the Carl Rosa Opera Company orchestra, that ‘with a name like his, he could go a long way in British music’.

Today, those words of banter would seem to have turned into the greatest understatement uttered during the past century, for that shy young man was indeed Gustavus Theodore von Holst.

History enlightens us that Holst was a humble man, whilst at the same time an extraordinary man and a truly great British composer. His magical Planets Suite, a work he had dreamt of years earlier whilst teaching at St Paul’s Girls’ School, Hammersmith and Morley College was finally completed in the peace and quiet of our town, Thaxted.

The Planets, by far his largest and best loved orchestral work, had its first public performance in London’s Queen’s Hall under the baton of Adrian Boult at the beginning of the twentieth century. His astrological orchestration was described as quite unlike anything else that had been previously composed. Music critics on both sides of the Atlantic became greatly enthused about his complex, yet astonishing score and his fame was established, for Holst had achieved a position that was rare for an Englishman, of becoming a really popular composer.

Holst was also a highly gifted teacher, whose contribution to the development of musical education in our schools is still to this day widely acknowledged, he was the man who put English music to the fore, most especially for us in Thaxted.

Born in the then unfashionable spa resort of Cheltenham in 1874, the Holst family had originally come from Latvia, then part of Russia, although culturally they were German. Gustav’s great- grandfather, Matthias, had met his wife Katherina when he had been a musician at the Imperial Russian Court in St Petersburg. He left Latvia, following its political upheaval, with his young family in the early 19th century and eventually settled in London during very exciting times, as continental musicians were in demand and well paid. Holst’s grandfather, Gustavus Valentin was a composer, harpist and pianist, whilst his father, Adolphus played the piano and the organ and also taught music.

Gustav’s newly-wedded parents, Adolph and Clare moved into 4 Pittville Terrace, now the home of the Holst Birthplace Museum in Cheltenham, just before the birth. With a pedigree to die for, the young Gustav seems to have got off to a difficult start, and was to have a rather sad childhood, firstly losing his mother at the early age of eight, then as a young man found that his poor physical disposition left him feeling weak, his eyesight was poor and he was to suffer from a respiratory disease, something that was to plague him throughout his life. I find it incomprehensible to understand just how one of Britain’s most famous composers emerged from such difficult beginnings.

It must be remembered that the world Holst was born into was a world completely different from our world today: it was before the age of the car, the aeroplane or even electricity, there was neither radio nor gramophone, television or even iPhones. Music-making formed the greater part of entertainment.

Early in his career he was to develop neuritis in his right arm curtailing his original ambition to follow in the family tradition and become a concert pianist. This ailment would necessitate the use of a distinctive grand piano with a specifically built light action. His two most talented and trusted literary assistants, Vally Lasker and Nora Day from St Paul’s School where a great help to Gustav when it came to copying out all his hand written orchestral parts as his composing came to the fore, and as we now know from listening to his Planets Suite, Gustav used every instrument in the orchestra and then a few more besides.

Throughout his life, illness would force him to seek short breaks from work, and with the growing number of conducting and teaching positions he was to accept as his career blossomed he needed to rest more and more. Luckily, one of his passions was walking in the countryside and it was on one of these rambling excursions through Essex that he stumbled across Thaxted, and this is where our never-ending legacy begins, for he was so taken with it’s charms that he vowed to return.

Within a year he had received an offer he could not refuse from one of his literary colleagues. Samual Bensusan: writer, journalist and music critic for the Illustrated London News and Van`ity Fair, and more importantly, one of the Countess of Warwick’s famous circle of literary and theatrical friends who enjoyed the Countess’ hospitality at Easton Lodge. Bensusan’s chronicles of rural life, most especially his portrayals of traditional Essex life and its characters still remain classics. This kind offer gave Holst the chance to escape the hustle and bustle of London and move into a peaceful Monk Street thatched cottage overlooking Thaxted. According to Holst’s daughter Imogen, her father loved working there at weekends and in the school holidays. In her memoirs, she recalls those early days in Thaxted as an extraordinarily quiet place in which to live, and that the family commanded such fine views across the valley towards Thaxted with its magnificent church spire standing proudly in the distance amongst the red-tiled roofs, with only the sound of singing birds and the gentle sighing of the wind in the trees for company.

The workings of the Countess of Warwick were to figure shortly afterwards in Holst’s life and our own, for it was at her command that Conrad Noel had been installed as vicar of Thaxted only a few years earlier, the two famous men were to finally meet face to face as Holst entered the Parish Church he had admired from across the scenic valley.

At the time of entering Thaxted, Holst still held the position of Director of Music at both St Paul’s Girl’s School, Hammersmith and Morley College for Working Men and Women on the Waterloo Road, London. Later he was to receive the great honour of being made a Fellow of the Royal College of Music, where he had studied as a young man and struck up his lifelong friendship with Ralph Vaughan Williams, who was to have a great influence upon both his music and career.

I’ve written before of this very important chance meeting in the Church between Noel and Holst in the Winter Issue No 80 in 2007, so I will not repeat myself, only to say his early teaching experiences gave him the complete understanding of the workings of a choir, which would have put him in good stead as he began the daunting task of grooming Thaxted’s factory and farm workers into a choir of repute that could, and would, proudly stand side by side with the girls of St Paul’s and Morley choirs in our own church during the first Thaxted Whitsun Music Festival in 1916. From these humble musical beginnings; music making and dancing, our unstoppable Festival concert scene and a Church renowned for its excellent musical tradition are now a way of life that we can all enjoy in Thaxted a century later.

A year later, Gustav along with his wife Isobel and young daughter Imogen along with their famous grand piano moved into The Manse in Town Street, then called ‘The Steps’. It was in these new surroundings that Holst would finally find the peace and tranquility that inspired him to utter those famous words, that he was now able to live the life he called ‘that of a real composer’.

It was at this grand house and walled garden in the centre of Thaxted that he would complete his most celebrated work. The Planets Suite, which since its inception has proved one of the most popular works by a British composer, and is now performed throughout the world by both amateur and professional orchestras and its influence on music, especially popular music for television, film scores and now computor games has been gigantic. Statistics state that the number of CDs sold of The Planets place it in the same league as Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, even the piano duet version first played by Lasker and Day has become appealing.

In fact looking through the records of the Festival, even as recent as 2009 Pascal and Ami Roge’ played the same Holst Planets duet for piano. The original copy, which had been lost for decades was found hidden away in a cupboard at St Paul’s School. In fact it was considered a major find within the music world, as it was signed by the composer himself and credited to Vally Lasker and Nora Day, his valued colleagues from the music department mentioned earlier in the article.

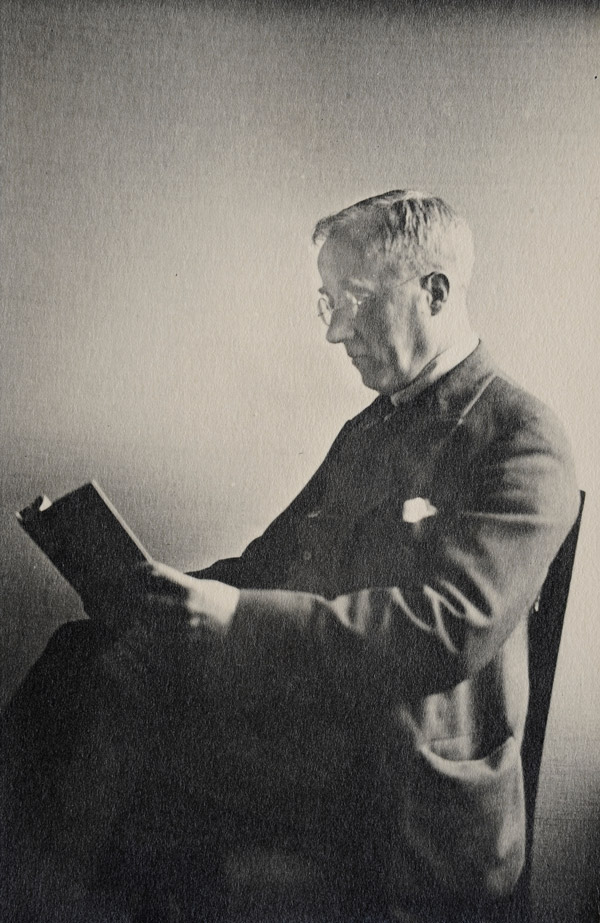

Way back in 1914, a young man called Jack Putterill, who was to become vicar of Thaxted many years later, first met and had the privilege of being taught by Holst himself at Morley College. But I’ll let Putterill tell you in his own words, as like his mentor Conrad Noel, he loved writing and I quote from his book. ‘One day I wandered into the magnificent church at Thaxted while the organ was playing. When the organist had finished playing – I think it was something from ‘Parsifal’, of which Holst was very fond – he turned round and with his characteristic smile looked at me through his strong glasses. Hullo, he uttered, what is your name and where do you live? I told him I had a cottage in Thaxted, but that I lived and worked in London. He then asked if I sang and what did I play? When I told him of my interest in music he asked me if I knew Morley College in the Waterloo Road, and could I go there tomorrow night and play in his orchestra. I told him I could, and I did.’

Jack not only joined the orchestra, playing the double bass, but also joined his harmony and composition classes as well as the choir. He explained in his book that as a teacher, Holst was always helpful and encouraging, and when he came across a bad mistake in our work he would turn round from the piano and ask, ‘Did you mean that?’ usually ending up by making some excuse: ‘Ah, well, Palestrina did it on one occasion.’

‘This all led up to a grand Whitsuntide Festival in Thaxted Church’. The very same Whitsun I mentioned earlier when Holst invited his two choirs and orchestra to Thaxted which now included Jack Putterill. Jack was duly ordained and would return to Thaxted as curate under Noel in 1925 and later as vicar in 1942. It was during this period that, Father Jack, as he was known to everyone, helped continue the legacy that Gustav Holst encouraged. In fact Father Jack went on to compose the three-part Mass entitled ‘The Thaxted Mass’ which has been sung in church ever since. His final words on Holst said that ‘Indeed he was a wonderful man, and long to be remembered in his immortal works’.

The true moral of Holst’s story is that although his orchestral suite has been a great public success, The Planets was hard won and born out of a feeling of utter failure and frustration that his earlier works had not been appreciated. Self-doubt, and an inner desire to explore and not accept received opinions, left Holst floundering and questioning the basis of his life. After his monumental opera Sita had just failed to win the prestigious Ricordi prize, you know the old saying, nobody remembers who finished second, he became more and more inconsolable. By 1912 his sense of failure was becoming acute, ‘Beni Mora’ had only a modest success and when his ambitious choral work ‘The Cloud Messenger’ only received a mixed reception he was distraught declaring that ‘I’m fed up with music, especially my own’.

This reaction was understandable, since these titles were some of his major works, most of which are now adored. We must remember, all had to be written on Sundays, after a tiring week teaching at various schools. In addition, we now know that the psychological burden placed of him for being financially beholden to a group of friends who believed in him, must have been enormous. Holst was one of only a few British composers who had no private income.

I believe Thaxted’s Church and its peaceful landscape helped bring Holst strength to continue his work, and it was here that he finally completed his unforgetable manuscript, the original which now rests in Oxford’s Bodleian Library.

Raymond Head, composer, teacher and above all else, a Holst scholar and one of the featured commentators in Tony Palmer’s brilliant film ‘Gustav Holst: In the Bleak Midwinter’, the premier of which I had the pleasure of attending, wrote in his new book entitled ‘New Light on a Famous Work’, that around 1912 Holst began looking seriously at astrology and found a book that had just been published entitled The Art of Synthesis, a most innovative astrological record, a book that is believed to have given Holst the inspiration to compose those picturesque descriptions of each of his seven planetary movements. Whatever his original thoughts were, the Planets are now considered a masterpiece that unleashed a startlingly original piece of music.

So a century later many people still consider Thaxted to be synonymous with music. From my own point of view, I recall as a young chorister singing ‘I Vow to Thee my Country’ on many Remembrance Day services in my local church and I remember my attention was always taken to the top of the music sheet where the uncommon word of ‘Thaxted’ caught my eye along with the composer ‘Gustav Holst’. Holst of course, I knew from my school music lessons, but I had to wait sixty years to put a face on the place, and did what so many people have done, I stayed.

Once here, you quickly realise that Thaxted Church and its music have certainly been inextricably interweaved through the centuries. Although Gustav Holst’s entrance brought more fame to the town, much earlier in the fifteenth century, locally born Robert Wedow became vicar of the Parish Church and had the distinction of becoming the first student to achieve a Bachelor of Music degree at Oxford and he also distinguished himself in literature and the arts. He later held office at St Paul’s and Wells Cathedrals and is in fact now remembered more for his poetry than for any musical compositions. He is still remembered in Thaxted Church by his memorial brass plaque in the Chancel, the only one to have survived the Reformation.

We had to wait another four and a half centuries before Holst found Thaxted, fell in love with the place and within the decade the seeds had been scattered and our musical legacy grew and grew.

I believe the music of Thaxted Church falls into two categories which are closely associated. Firstly there is the music of the Liturgy we sing every Sunday. Each century that passes we seem to add to the rich heritage of English Church Music, even during this passing year we have had the experience of hearing three beautiful new pieces composed especially for our church, one from our Director of Music, Christopher Bayston who wrote a new anthem entitled ‘Soul of the World’ that had its first performance during the re-dedication service of the Lincoln Organ and another from local musician, Jake Walker named ‘The Holy Trinity’, a piece that had been specially commissioned by the Lincoln Organ Restoration Committee and played by celebrated organist Anne Page on the newly restored organ during her wonderful recital.

The third piece had its first hearing at November’s touching Remembrance Service inside the packed church, when midway through the service following the reading of the names of the fallen, the floating poppy’s, the silence that seems to last longer each year, followed by the Last Post and the Kohima Inscription; cue it was time for our guest soloist and co-writer of this new and most beautiful sensitive piece of music, for Lisa Peretti sang ‘My heart goes with you’, those of you who have had the pleasure of hearing Lisa’s wonderful voice before, and here I must admit I am her number one fan, this girl has the voice of an angel and also a heart to go with it, for in her spare time between looking after her family and pursuing her professional career she volunteered to become musical director of the Military Wives Choir at Carver Barracks. I must also mention Jerry Piger who co-wrote a number of Lisa’s songs from her latest album and of course ‘My heart goes with you’, and as she always reminds me, ‘her creative partnership with Piger is a gift from God’. I can think of no better place for its debut. We closed the service with Holst’s legendary ‘I Vow to thee my Country’, that left me with tears in my eyes, I can’t vouch for the rest of the congregation. Music can help bring out all our inner emotions, whether its joy or sadness.

The second category is making music for music’s sake. Its nearly one hundred years since Holst first introduced Thaxted to famous orchestras, soloists and conductors, all performing in our own Parish Church, and we have been carried along by the glory and fine example set by Holst, who we must remember, was particularly anxious to encourage young musicians.

Since those early days The Thaxted Festival has brilliantly continued this splendid tradition, for every new season we see and hear a multitude of Youth Orchestras and Choirs, while not forgetting the occasional Opera, School Pageant and even a touch of Traditional Jazz, whilst not forgetting that splash of colour from our Morris Dancers.

As one of our church banners reminds us ’The aim of Music is the glory of God and pleasant recreation’. For many years people have flocked to Thaxted to experience the true meaning of those words of Bach. You might think that the likes of Nigel Kennedy, John Lill, Jamie Cullum, Nicola Benedetti, Sir John Dankworth, Lesley Garrett, Sir Adrian Boult and Yehudi Menuhin would be an odd mix, but believe me they all work at the Festival.

It all started with that joyful first festival over the Whitsuntide weekend of 1916, described by Holst as ‘four days of perpetual singing and playing’ in the church, in houses, in gardens and in the street. He had invited his choirs and orchestras of St Paul’s and Morley Schools to join the Thaxted choir in making music. The results of that holiday weekend are now legendary, the festivals continued until 1918, although Holst’s association with Thaxted lasted until 1925.

Holst and Vaughan Williams remained friends for life, both were collectors of English folk music which inspired so many of their compositions. Vaughan Williams would often sit at the Lincoln organ and play, whilst Holst would take the baton and conduct the choir, sometimes their roles were reversed.

In a letter to his dear friend and fellow composer W.G.Whittaker, written after that eventful weekend, he stated that the concert, in fact the long Bank Holiday Weekend had been a feast – an orgy. Four whole days of perpetual singing and playing either properly arranged in the church or impromptu in various houses or still more important in ploughed fields during thunderstorms and even on the train home. It has been a revelation to me, he wrote. And what I shall never be able to persuade you is that quantity is more important than quality. We don’t get enough. We practise stuff for a concert at which we do a thing once and get excited over it and then go off and do something else. Whereas on this occasion things were different. There were about 15 Morleyites, 10 St Paul’s girls, 10 outsiders and 10 Thaxted singers. The latter did grandly. Most of them work at a factory here and I have been asked to give them quicker music next year. It seems that they sang all day, every day at their work for months and the slow notes of the Bach chorals seriously affected their output!

In a later letter to Whittaker he pondered with the idea that music should either be done in a family party or in a church. He wrote: I feel this more and more – it was Whitsuntide at Thaxted that convinced me first. One loses one’s sense of individual personality and when that happens music begins’. Anyway he concludes, ‘Anyhow them’s my sentiments’.

Having suffered a nervous breakdown in 1925, he took a break from work and rested back in Thaxted and finally moved down the road to the Easton’s. He kept in touch with his friends and occassionally played the organ, usually at Christmas. Having recovered, he left for America where he had been appointed Lecturer in Composition at Harvard. Unfortunately he became ill and returned to England. Although he continued to compose, he was to lead the latter part of his life as an invalid. In 1934 he entered hospital and had an operation for a duodenal ulcer, but unfortunately died two days later and his ashes were interred in Chichester Cathedral.

Image credits:

— The Holst Birthplace Trust, The Cheltenham Trust and Cheltenham Borough Council.

— Michael Bailie.

– CONTINUED SUPPORT

Donations

The Lincoln Organ is now a fine working instrument and has been played at various recitals and events by some truly great organists, however it still needs regular maintenance, any donations would be so gratefully received.